Sleep Is Not A Weakness!

Sleep is not a weakness!

Author: Ojas Deshpande, MD candidate, CUSM School of Medicine | Arrowhead Medical Center

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Alan Hall II, MD | Associate Professor | U of Kentucky College of Medicine

“Just one more chapter,” I said to myself as I looked grudgingly at my computer screen clock displaying 1:45 AM. I was tired and decaffeinated as I had stayed away from coffee after 10:00 PM to help allow for some sleep. I had to wake up at 6:00 AM, so mental math told me that I could still get a solid 4.25 sleep hours.

I toyed with the idea of closing my laptop, knowing I would quickly fall asleep. However, as a second year medical student, tomorrow was full of even more responsibilities. I knew I could not get behind. It was now a menacing 2:00 AM. The clock stared back at me, judgingly… and I shuddered to think about waking up in just a few hours.

Sleep and sleep hygiene are critical components of wellness that we in the medical community struggle to incorporate into our daily workflows. Whether it be systemic difficulties (such as continually alternating night and day shifts) or the waves of patients flooding hospital systems during the pandemic, sleep remains a marginalized element of wellness regimens. Sleep deprivation has severe consequences, including research showing increased rates of medical errors. To limit fatigue and resultant errors for pilots, the aviation industry has limited prolonged periods in flight. Despite this, medicine remains recalcitrant to place a greater emphasis on sleep. Given these observations, I interviewed physicians on the frontlines as well as an expert on sleep medicine and neurobiology to gain their perspectives on sleep and wellness in medicine.

***

Perspectives from an IM resident: Dr. Aram Namavar, MD, MS | UCSD-SOM

OD: How pervasive do you think burnout is within your specialty, and do you think sleep has anything to do with it?AN: Burnout is widespread in medicine, and certainly so in hospital medicine. Unfortunately, it does not receive as much exposure as it should. A study recently highlighted that the “7-on, 7-off” model may be contributing to burnout, and this in part may be due to the constantly adjusting sleep habits. I can see how poor sleep can thus contribute to increased rates of burnout. However, in residency if you have one bad night, you can often take more time to sleep the next. Programs have begun to take notice and are making changes.

OD: Would you say you have good sleep hygiene, and do you think sleep hygiene is receiving importance in the hospital medicine community?

AN: In general, residency involves lengthy shifts and puts a strain on sleep time. I try to ensure that I put an emphasis on sleep, because if not it will cause a downward spiral in productivity. In my opinion, the residency environment provides more regimented hours that permit you to plan your schedule more easily. However, I do not think sleep hygiene has been addressed in the medical community and we can do more to incorporate it into wellness curricula.

OD: Do you think the pandemic has contributed to burnout, and has it impacted your sleep in any way?

AN: Certainly. The abilities to socialize and travel are important and the lack of being able to do so is frustrating, but understandable. I can see how this contributes to accelerating burnout. I try to make sure I have safe ways to combat stress, such as visits to the beach and regular meditation. Increased patient volume has made it tough to get good sleep regularly, but I try to make sure I stick to some basic rules. For example, prior to transitioning to night shifts, I try to stay up as late as possible the night before.

***

Perspectives from a Med/Peds Attending: Dr. Alan Hall, MD | U of Kentucky-COM

OD: Have you found specific elements within hospital medicine that contribute to burnout?AH: The high-intensity time on clinical service can make it difficult to keep up with non-clinical work, making it constantly feel like I am catching up on my non-clinical weeks. Night/evening shifts contribute to poor sleep, especially when flipping from one shift to another. This is not specific to hospital medicine, but the healthcare system issues that force us to do extra work that should not be necessary for patient care (e.g., talking to an insurance company to approve care that is the standard of care) certainly do not help and can even keep us awake at night.

OD: Would you say you have good sleep hygiene?

AH: I think my sleep hygiene is reasonable and better than it used to be, as I get around 7 or so hours of sleep per night. I think getting to bed earlier has been aided by our toddler, since she has an early, automatic alarm clock that encourages us to avoid staying up late. We do not watch TV in the bedroom and generally I read on my Kindle before falling asleep. I can work to avoid my phone while lying in bed!

OD: Do you believe prioritizing sleep and sleep hygiene has been given attention in the hospital medicine community?

AH: I think it is something that is receiving a good push for our patients –to promote their sleep, which is vitally important. But I think we, as physicians, take for granted how important sleep is for our own wellness. I think poor sleep makes everything harder, including contributing to burnout.

***

Perspective from Dr. Ruth Benca, MD, PhD | UCI-SOM

Dr. Benca is the chair of Psychiatry and Human behavior at the UCI school of Medicine. She has a broad background in basic and clinical sleep research.

OD: Do you believe sleep hygiene is an important component of achieving high quality sleep?RB: Sleep hygiene is the baseline set of activities for which good sleep health starts. Sleep is regulated by two processes; 1) Sleep deprivation: the longer you are awake the more you need to sleep & 2) Circadian rhythm: Regulation of sleep by the circadian clock and the light-dark cycle.

Sleep is optimal when you have a REGULAR cycle, so that the homeostatic and circadian can work together. We are seeing the detriments of the pandemic manifest in the form of poorer sleep quality and delayed-phase sleep patterns. Sleep hygiene acts as a protective factor that helps us attain normal sleep. It is something we should practice regularly, like exercising. However, sleep hygiene is not a cure for sleep problems.

OD: Why are sleep and sleep-related disorders underdiagnosed and under-recognized in the medical community?

RB: This is a multifactorial problem. When we are asleep, we are in a vulnerable state. This is true for all creatures. Thus, there is already an instinct to remain awake in times of stress. Couple this with the idea that our society has a “24-hour” non-stop mindset, with constantly streaming entertainment. In addition, more people are becoming obese and have comorbidities that contribute to worsening sleep disorders. In many cases, not sleeping is considered a badge of honor – sleep is perceived as a waste of time. Finally, physicians are not that well educated about sleep. We spend 1/3rd of our lives sleeping but medical school curricula only spend a few hours talking about it. If physicians remain unaware, it is difficult to identify sleep disorders and understand their underlying health risks.

OD: One of your studies highlights the relationship between insomnia and depression. Do you think the pandemic has made this worse?

RB: We now know that there is an increasing rate of depression among physicians, and sleep disruption as well as chronic insomnia can contribute to its development or exacerbation. The pandemic has exacerbated risk of burnout, depression, and suicide by affecting both sleep and psychological function.

When you are sleep deprived, you tend to overreact to negative stimuli. In the middle of the night, your mood set point also tends to be more negative. Thus, the disruption of homeostatic control and circadian rhythm can result in mood dysfunction. There is a lot of data highlighting that physicians working longer shifts tend to make more mistakes and engage in more risky behaviors.

OD: Do you think there are ways we can mitigate these issues?

RB: There are things we can do to help re-entrain their circadian rhythms. For example, night-shift workers must maintain the same sleep period and pattern even on their days off, to minimize disruptions. When transitioning, we try to entrain the circadian rhythm by employing techniques including timing of light exposure, use of melatonin and arranging the day’s workflows around sleep. At least 10% of the population cannot physiologically handle shift work well. One of the things to consider when working shifts is whether your body and mind are truly able to handle the shift timing. Many people physically require more sleep to function at baseline. Some people truly need 9-10 hours of sleep, and you must identify your capacity.

Residencies have started to do a better job about enforcing work limits on trainees, however there are no such limits after training. It begs the question about whether attending physicians should also have duty-hour limitations, like the transport industry and others.

OD: How can we recognize our physiological sleep limits, and acknowledge these limits in a constructive way?

RB: Work in the sleep field has shown that the more sleep deprived you are, the less able you are to judge that you are sleep deprived. It is important to realize that you are not weak by accepting that you require a certain amount of sleep. It is a fundamental element of your physiology and depriving yourself doesn’t make you superior. In medical practice, we all have nights that we are sleep deprived. That is why it is important to make sure to schedule plenty of time to sleep on other nights during the week. Young adults require 7-9 sleep hours and 6-8 hours as you get older. You need MORE time in bed than that, to get that amount of time sleeping. Like exercising, you may not be perfectly scheduled every day, but you want enough good days where you are not staying up late.

***

The unforgiving din of the alarm startled me out of bed. The clock read 6:00 AM in angry, red characters. I sat up, cold and irritated. Looking back at the warm embrace of the bed that I left just a few moments ago, I made a promise to come back to bed at a reasonable hour – this time I meant it.These interviews taught me worthwhile lessons about valuing sleep and wellness. I now recognize that the luminous gratification of working more by constantly compromising my sleep, conceals the long-term pathologies that lurk in the shadows. Setting aside time in my schedule for sleep is not hedonistic or weak. Rather, it is a physiological necessity that will ensure my peak mental function - both at the library today and the patient’s bedside tomorrow!

I would like to sincerely thank Dr. Aram Namavar, Dr. Alan Hall, and Dr. Ruth Benca for taking time out of their busy schedules to share their perspectives with me on this under-appreciated topic. Their insights have provided me with a pulse on the perception of sleep science in medicine and physician wellness!

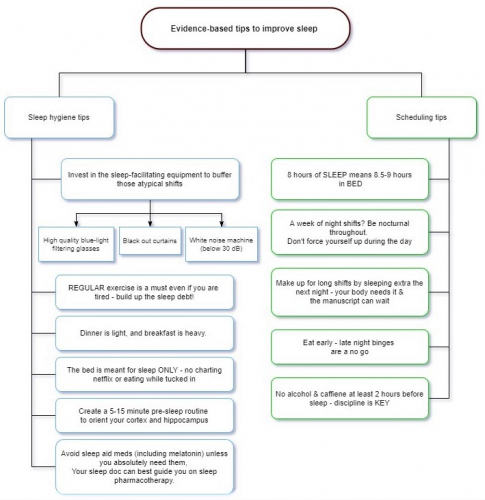

Tips on how to achieve quality sleep:

This diagram is a brief compilation of tips that I compiled throughout my conversations with Dr. Benca, Dr. Hall and Dr. Namavar, as well as from the scientific literature.